Nimpressions

Python is my go-to language for personal projects, and even client projects when I can get away with it (though usually those are Windows based and within the .Net ecosystem, so I stick with C#). However, it often gives me pause to be using one of the slowest and least energy efficient languages available - I might do another post about that, but suffice it to say that it doesn’t align with my values to needlessly waste resources.

The ideal would be a language that’s as easy to write as Python, but as fast and energy efficient as C, or close to it. Well recently I came across a language that claims be both of those things: Nim.

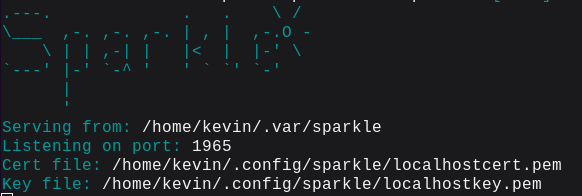

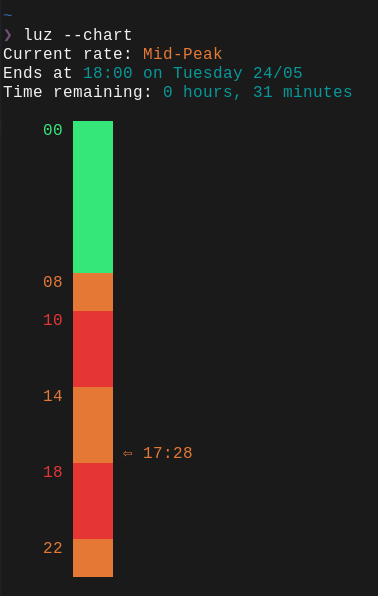

I put together a simple command line application (named Luz) in Nim this week in order to try it out. Appropriately enough given my reason for trying Nim, it just shows the current electricity rate band, and optionally a chart, because where I live there are two peak periods during the day when it is better not to do anything power-intensive. I went on to make a start on a very simple Gemini server called Sparkle, which is still a WIP. Here are some of my thoughts on the experience as a mediocre developer with some Python and C# experience.

choosenim

Nim has a tool for installing its toolchain and and switching between different versions of the compiler, similar to pyenv. Unfortunately it didn’t work for me on Pop! OS 22.04 due to it having too new a version of libssl. I was able to install the Nim compiler manually easily enough by just downloading the tarball and copying the contents to an appropriate location, and then adding the bin directory to my path. There was an install script in the tarball but it didn’t copy everything for some reason.

Not a great start, and I’m not sure what I’m missing out on by not using choosenim, but I can figure that out later if I continue using the language.

Typing

Static typing is something I’m well used to from C# of course, but I don’t engage with Python’s type hinting at all. There is type inference in many situations, and many familiar collection types such as sets, tables, sequences and tuples which are as convenient to instantiate as their Python equivalents, though of course you can’t mix unrelated types within them (aside from tuples)(and why would you do that anyway, you monster). Mostly it is just convenient to know at compile time where there are type mismatches, rather than hearing about them at runtime or just getting weird behaviour.

Nim is only very minimally object-oriented. There is inheritance, but not multiple-inheritance, mixins, or anything resembling the interfaces or traits of other languages. This is probably one of the most concerning aspects of the language for me. It seems like it will inevitably lead to repeated code at some point if procedures can’t accept abstract interfaces as input instead of concrete types.

On the other hand I try to steer away from an object-oriented style in Python unless it really makes sense for the problem I’m working on. In Luz, the classes I created were little more than structs, with no inheritance required, and that’s perfectly sufficient for many problems.

There are also apparently libraries that create a means to specify interfaces using meta-programming, but that’s not something I’ve explored yet.

type

Holiday = ref object

date: DateTime

localName: string

name: string

countryCode: string

fixed: bool

global: bool

counties: Option[seq[string]]

launchYear: Option[int]

var holidays = initTable[int, seq[Holiday]]()

proc isHoliday*(d: DateTime): bool =

result = false

# This will occur if API key was not provided

if not holidays.hasKey(d.year):

return result

for y, h in holidays[d.year]:

# global indicates that the holiday applies to the whole country

if h.global:

if h.date.yearday == d.yearday:

result = true

break

Uniform Function Call Syntax

This is really neat - any procedure or function can be called as if it is a method of the type of its first parameter.

proc sendErrorResponse(

requestSocket: AsyncSocket,

code: StatusCode,

meta: string

) {.async.} =

await requestSocket.send(&"{ord(code)} {meta}\r\L")

proc processRequest(requestSocket: AsyncSocket) {.async.} =

...

# These calls are equivalent

await requestSocket.sendErrorResponse(

StatusCode.notFound,

"Not Found"

)

await sendErrorResponse(

requestSocket,

StatusCode.notFound,

"Not Found"

)

This means that any type can be “extended” in a sense just by writing procedures with that type as the first parameter, no need for sub-classing or a special extension method syntax.

Blocks

One neat little feature is that you can open a new code block anywhere, with or without a name, and as well as being visually separated from the code around it it will have its own scope. A break statement will break out of that block, but not the containing one.

I didn’t find much use for this in either of the projects I’ve worked on so far, but it’s definitely something I can see being useful for longer procedures and certain control-flow situations.

Closures

Nim supports passing around references to procedures, which allows for a number of neat constructs, including closures. The below procedure creates a closure that animates a spinner when called in a loop while waiting for an IO operation to conclude. It contains everything it needs, including a constant.

proc getDisplayProgressClosure(): proc() =

const phases = ["🮪", "🮫", "🮭", "🮬"]

var lastTime = now()

var phase = 0

var initial = true

proc displayProgress() =

let elapsed = now() - lastTime

if elapsed.inMilliseconds > 100 or initial:

lastTime = now()

if not initial:

erasePrevious

initial = false

styledEcho(

fgGreen,

&"{phases[phase]}",

fgCyan,

" Retrieving holidays..."

)

inc(phase)

if phase > phases.high: phase = 0

result = displayProgress

Templates & Compile Time Execution

One of the most exciting features of Nim, for me, is the ability to execute code at compile time, and otherwise manipulate the final state of the code.

For example to embed a file in a binary in C# you have to set a property against the file in the IDE (or maybe in the project file) to make it an embedded resource, and then do some reflection to pull it back out at runtime. In Nim, you can just call readFile and assign the result to a constant.

const DEFAULT_BANDS = readFile "./config/bands.json"

const DEFAULT_CONFIG = readFile "./config/luz.toml"

There is also a compile-time branching statement, when. This is similar to the pre-processor #if in C#, or #ifdef in C, but it fits more naturally with the rest of the code.

Templates allow you to insert specified code in other parts of the codebase, with substitutions, before compilation. One use for this is as an alternative to short procedures, so the code gets inlined, saving a function call.

I feel like I’m only at the start of getting my head around this feature. I thought it might be a good way to output variations of a procedure for operating on different types, but I’m not sure the result is readable or concise enough to be worthwhile:

template createGetSetting(

valueType: untyped,

argValueTypeGet: untyped,

envValueTypeGet: untyped,

confValueTypeGet: untyped

) =

proc getSetting(

args: Table[string, Value],

arg: string,

conf: TomlValueRef,

confSection: string,

confKey: string,

env: string,

default: valueType

): (valueType, ConfigVariableSource) =

result = (default, ConfigVariableSource.Default)

if arg in args:

if args[arg].kind != vkNone:

return (

argValueTypeGet(args[arg]),

ConfigVariableSource.CommandLine

)

let envStr = getEnv(env, "")

if envStr != "":

return (

envValueTypeGet(envStr),

ConfigVariableSource.Environment

)

result = (

conf[confSection][confKey].confValueTypeGet(),

ConfigVariableSource.ConfigFile

)

proc splitOnComma(val: string): seq[string] =

result = val.split(',')

proc getStringSequence(value: TomlValueRef): seq[string] =

let values = value.getElems()

result = @[]

for v in values:

result.add v.getStr()

proc parseIntArg(val: Value): int =

result = parseInt($val)

createGetSetting(string, `$`, `$`, getStr)

createGetSetting(int, parseIntArg, parseInt, getInt)

createGetSetting(bool, toBool, parseBool, getBool)

createGetSetting(seq[string], `@`, splitOnComma, getStringSequence)

The result of the above code is four different procedures called getSetting which look for a setting in the command line arguments, an environment variable, or a config file, and return it as the expected type.

Even though the above code is a mess and I’m probably going to rethink it, I will say this - writing the template was surprisingly intuitive.

Nim’s meta-programming features become even more powerful with macros and pragmas, but I haven’t really gotten into them yet so I can’t say much about them.

Standard Library

There’s some pretty great stuff in the standard library, including very easy to use asynchronous http and networking libraries, and parsers for a variety of text-based file formats. Everything seems to be appropriately cross-platform as well. I haven’t got much else to say about it!

Python Modules

Something I’m always looking out for in a language is the ability to write Python modules in it. There seem to be a couple of Nim libraries for doing this, both based on an underlying nimpy library. They both look incredibly easy to use, but notably the support for exporting Python classes in nimpy seems to be experimental. It is also a bit unclear how it deals with Python objects as parameters of procedures rather than basic types.

My only point of comparison is Cython, which is a really cool project that compiles Python code to C, and includes an optional extended syntax for optimisation, which is essentially writing C code but with a Python-like syntax. As cool as this is I think the breadth of options is confusing, and when you get down to writing optimised routines things start to break in very unhelpful C-like way - i.e. successful compiles and unceremonious runtime segfaults.

I much prefer the idea of writing modules in a language that is its own thing, and with Nim being as easy to write as it is, I’m excited to try it for this purpose.

Conclusion

I didn’t perform even rudimentary benchmarks, but I think it’s safe to assume that anything written in Nim will be faster than the equivalent Python code. Luz runs instantaneously, and Sparkle responds to requests almost instantaneously as well. Neither of them are doing anything that I wouldn’t expect Python to do at an acceptable speed under the same circumstances, however.

One thing about Nim benchmarks that I have seen is that they are generally performed with the -d:danger compiler flag, which disables all runtime checks. This is done in the name of “fairness” in comparison with C, but it doesn’t really seem fair to me if the norm for the language in production is -d:release.

I definitely found Nim very natural to develop in. Unlike Rust, which I also tried (failed) to learn recently, most of the concepts were already familiar to me from other languages, and the syntax was also very familiar. I often found myself writing correct Nim code first time, and where I made mistakes they were flagged during compilation in a way that was easy to understand. Runtime errors are also handled relatively gracefully - no segfaults even though Nim compiles to C, like Cython does.

Overall, a very interesting language that I look forward to doing more with.