The Ancaps

Much has been said already about the fact that HBO’s documentary series “The Anarchists” is not really about anarchists, and by people far more capable of making the argument than I. Nonetheless, I do have some thoughts on that and other aspects of the documentary.

My overall impression of the documentary is that it is philosophically vacuous and insincere. “Anarchism” is defined superficially by the characters in what is essentially an examination of interpersonal drama. The history of Anarchism proper, and its inherent conflict with capitalism is not explored, but neither, really, is “anarcho”-capitalism or the ideas behind it, on their own terms or otherwise. The community is simply mined for drama and spectacle. The main propaganda points of the doc lie in the fact that “freedom” is just implicitly associated with laissez-faire capitalism, and the appropriation of the word “Anarchism” and anarchist symbols by the right, a long-running project.

The Inherent Contradictions of Ancapitalism

Though the documentary has little interest in examining them, the cracks and contradictions in the ideology do show through.

I think it is safe to say that everybody who enthusiastically embraces an extreme capitalist ideology thinks that they are, or will be, the boss of whatever enterprise they are involved in. Of course this produces tension when it turns out that somebody’s property rights, and a lack of any critique of property or the hierarchies it produces, makes subordinates of people who consider themselves entitled to be in charge.

The Anarchapulco conference that the documentary focuses on was not organised in a non-hierarchical manner from its conception because anarcho-capitalism does not renounce all hierarchies, only the existence of the state. Jeff Berwick, the founder and apparent “owner” of the conference behaves throughout as if organising the conference is something that an employee should be doing on his behalf, with his own role limited to giving a keynote, receiving adulation, and partying.

The first such employee we are introduced to is Nathan Freeman, who apparently had a leading role in organising the conference for several years after attending the initial one. It seems to me that Freeman thought himself and Berwick were partners in the endeavour. Berwick obviously saw things differently, and replaced Freeman in 2019 with an outsider.

Tragically, it seems like Freeman couldn’t cope with this humiliation, and essentially drank himself to death. Berwick didn’t even offer condolences to his family, because he’s an enormous piece of shit.

There are a number of aspects to the circumstances of his death that a documentary that was an honest examination of anarcho-capitalism would interrogate. He fell victim to a crypto scam shortly before becoming sick. What is the anarcho-capitalist perspective on this kind of crime? What does history tell us about private money and its effects on society? It’s glossed over as an unfortunate, unavoidable risk of “freedom”. He had no insurance, and his family had to rely on charity to pay his medical bills. What is the anarcho-capitalist perspective on the provision of healthcare? The question is not even asked.

Interestingly, John and Lily, the young couple who flee to Mexico after being arrested on drug traficking charges, do form a critique of the hierarchical, commercial nature of the Anarchapulco conference, and start their own alternative conference called Anarchaforko. It’s a bit unclear the extent to which this is organised at all rather than just people showing up and doing whatever, but it seems to work, and I would love to hear more about how this fits with their apparent objectivist leanings. But of course we get nothing like that.

Stateless in Mexico

Probably the funniest aspect of the documentary for me is that the participants seem to think that Mexico is “more anarchist” than the US, just based on the general vibes. Mexico, of course, does have a state, and I don’t have any reason to think that it is “less of” a state than that of the US.

I think this sense of “anarchiness” is probably the result of a few different factors. Many of the ancap immigrants are relatively wealthy, and apparently speak little or no Spanish. They are essentially just squatting on top of Mexican society, with no real connections to it, and using their wealth to extract what they need from it. The Mexican state protects them, as states generally protect the wealthy. They have little negative contact with it, and don’t hear about other people’s negative interactions with it as they would in the US, because they don’t speak the language. They’re just living in a little fantasy colonialist bubble.

Some members of the community are not so well off, and they do have negative experiences with the Mexican state, ranging from dealing with bureaucracy to being pursued, threatened and arrested by the police.

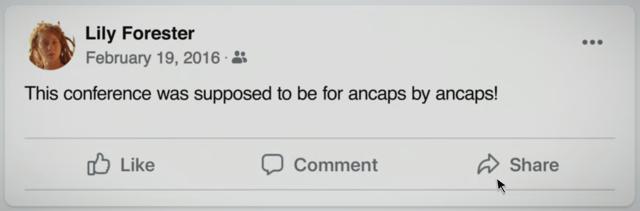

Although Lily Forester is a member of the latter group, it is her concluding statement on the existence of the state that best sums up the general attitude:

I just want to be left alone, like, a state can exist if it’s going to leave me alone.

On a personal level I can relate, especially given what she went through, but it’s a far cry from the moral clarity of this Fannie Lou Hamer quote:

Nobody’s free until everybody’s free.

Any meaningful conception of freedom can’t ignore that other people are subject to repression or exploitation, but that is exactly what these ancaps constantly do - the Mexican state is fine because I’m a rich foreigner and it leaves me alone, capitalist hierarchies are fine because I’m on top of them.

M’Aidez!

As I mentioned above, the primary participants in the documentary fall roughly into two groups - one comprised of relatively wealthy entrepeneurs like Berwick and the Freemans, and the other of struggling working class people like Lily Forester and John Galton, Jason Henza, and Paul Propert.

Though both groups are motivated by more-or-less the same ideology (Henza claims himself and Forester are not ancaps, but I don’t really see much distinction between anarcho-capitalism and voluntaryism or agorism myself), the differences between their circumstances is stark. The wealthy run their businesses from their lavish properties while the rest do odd jobs, deal drugs, and otherwise hustle to survive while living in marginal circumstances. As Thaddeus Russell notes:

It’s very easy to escape governments, banks and states if you’re already a Bitcoin millionaire. If you’re like John and Lily, you’ve got no resources, nothing, it’s hard, it turns out, and dangerous, in fact, to be an anarchist in Mexico.

The tension between these two groups is discussed at several points. The drug dealing and other illegal activity (like the theft of a Bitcoin ATM) are an inconvenience for the wealthy, and the unhinged Paul Propert is a potentially deadly threat to everybody, but they have no solutions. Everybody is just on their own to fend for themselves.

The documentary explores the backgrounds of Galton, Forester and Propert in some detail and finds a variety of broken homes, substance abuse problems, and other traumas. Like the characters themselves, it doesn’t seem to consider for a moment that the source of these traumas is the very social system that they cling to so tightly.

Nonetheless the clearest critique the documentary has for the anarcho-capitalist project is the lack of solidarity and support that those lacking means, and in dangerous circumstances, receive from the community, and what this would imply for an anarcho-capitalist society. Erika Harris, who ends up feeling alienated from the community and leaving Acapulco for Belize, makes this plea for mutual aid after John Galton is murdered, and Lily and Jason are on the run:

There’s an emergency among us, how will we respond? With shelter, with safehouses, with passage over borders if necessary … We need each other to get this done. I mean, we need each other just to move one inch forward.

Unfortunately, her plea seems to have fallen on deaf ears.